SOUTH AND ABOUT!

With the aims of opening informal communication channels among graduate students of the New York Area focusing on topics related to the arts of Latin America and the Caribbean, IFA Latin America has created South and About! This workshop series is structured as a student-run initiative striving to open a casual space for dialogue and peer-to-peer feedback on the work in progress of emerging scholars in our field. Our thematic focus is broad and welcomes interdisciplinary methodological approaches, including, but not limited to, temporal and geographic proposals of an innovative nature. Through this lens, we seek to foster and strengthen further interconnections within our communities via creative intellectual exchanges.

We will meet on the dates specified below from 6:30 to 8:00 PM in the Basement Seminar Room at the Institute of Fine Arts, NYU.

April 15

South & About! is a student-organized research workshop on the arts from Latin America and the Caribbean. This program invites graduate students and emerging scholars in art history and related disciplines to participate in informal discussions amongst their peers.

Setting the Clock on Time for Puerto Rican Modern Art

Carlos Ortiz Burgos, PhD Student, The Graduate Center, CUNY

The historiography of Puerto Rican modern art was developed in the 1980s, following a model that led to an erroneous conclusion: that most artists completely rejected modernism until the 50s, which delayed the development of modernism on the island. In this paper I argue the opposite: Puerto Rico is the first space in the Americas that received the seed of modernism, which started a slow but steady process of transformation of painting.

Puerto Rican art historians established it was not until the late 1930s that the first artists started experimenting with new trends. But Puerto Rican painter, Francisco Oller y Cestero was one of two artists from the Americas who was part of the impressionist circle in Paris and the only one who returned home to teach. His students would paint au plein air, with a loose and short brushwork and capture the potent Caribbean light, and so would most of the artists of the following generation. Moreover, since at least 1904, artist Julio Tomás Martínez started experimenting with a sui generis symbolist style, so distinctively modern that has been mislabeled as surrealist.

One of the pioneers of Puerto Rican art history, José Antonio Torres Martino based his historical scaffolding on Antonio S. Pedreira’s texts about Puerto Rican literature, which made him wonder why early 20th-century painters were not as risqué as writers. He based his solution on identity politics, arguing that Oller sacrificed his career as an impressionist (following Osiris Delgado’s theory), to paint easy-to-understand artworks that reflected his patriotic duty. By the same token, when Torres Martino came across a clearly modernist artist like Martínez, he called him “a lost soul” (descarriado, in Spanish) for painting singular subjects in a unique style.

Centering my study on the artworks, through social, formal, and stylistic analysis, I demonstrate that impressionism changed Puerto Rican painting in such a way, that even those who actively opposed modern art, could not avoid practicing some of the techniques that resulted from this paradigm shift. Furthermore, I argue that because art history, as a discipline, was in its early stages during the 1980s in Puerto Rico, Torres Martino collapsed form and content in his analysis, thus ignoring the technical changes in the artworks of which he only judged their subjects.

It has been over 20 years since Nelson Rivera’s seminal book “Con Urgencia” in which he dismounted the discourse that included what he called an “unsound theory” that has been “repeated ad nauseam” and which “successfully contributes to offer a distorted image of Puerto Rican art as an art incapable of dialoguing with modern art” (22–23, my translation). My research picks up the pieces Rivera deconstructed to build a new history of Puerto Rican modern art in the light of new data. Just like the writers, Puerto Rican painters started an artistic development with proto-modernist techniques in direct dialog with their political interests, as these were not mutually exclusive. In this way they created a path from impressionism to cubism, surrealism, Mexican muralism, and abstractionism throughout the first half of the twentieth century. Hence, modern art in Puerto Rico was never late, in fact, it started early.

A Wandering Pavilion: A Revelation, A Failure, and the Intermittent Participation of Mexico at the Venice Biennale, 1950-2015

Rodrigo Guzman-Serrano, PhD Student, Cornell University

In 1950, Mexican artists Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, and Rufino Tamayo represented Mexico at the 25th Venice Biennale in an exhibition that Rodolfo Pallucchini, then general secretary of the biennial, described as “a true revelation” [una vera rivelazione]. Despite this initial success, as well as an offer to build a permanent pavilion at the Giardini in 1951, from 1952 to 2007, the presence of Mexico at the Biennale became irregular, sporadic, and, at times, completely absent. Given the significance of Mexican art, particularly Mexican muralism, in the international scene of modern art throughout the twentieth century, it seems incongruous that the overall participation of Mexico at the Venice Biennale has been inconsistent, at best occasional. Only since 2007, with an exhibition by Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, has Mexico had a continuous national pavilion in Venice. After the “revelatory” pavilion of 1950, why did Mexico not secure a long-standing participation in Venice? Rather than offering a definitive answer to this question, this paper delves into the historical, political, and economic circumstances of the sinuous journey to establish a Mexican presence in Venice, with an emphasis on the 1950 pavilion and the post-2007 pavilions, particularly the 2015 exhibition Possessing Nature by Tania Candiani and Luis Felipe Ortega, which marked the first time Mexico was assigned a long-term location in one of the central venues of the biennial, the Arsenale. Through an analysis of artistic identities in Mexico as well as their official governmental support, this paper argues that Mexico’s presence at the Venice Biennale can be seen as an indicator of the way different artistic projects have been articulated at home at the conjunction between the local and the global.

—

January 29

South & About! is a student-organized research workshop on the arts from Latin America and the Caribbean. This program invites graduate students and emerging scholars in art history and related disciplines to participate in informal discussions amongst their peers.

Hemispheric Diaspora and Collective Resistance in Wiki Pirela’s artwork

Oriana Mejías Martínez, PhD Candidate, The Graduate Center, CUNY

This presentation explores new influences that have emerged within the visual culture of Chilean territories, associated with overlooked routes of diaspora and forced migrations (Raiford and Raphael-Hernandez 2017). Wiki Pirela exhibits Universo 11 (2023) and ¿Cuánto cuesta el cielo? (2023) are evocations strategized to address Hemispheric migration/movement and complications of home. Universo 11 stretches across space and time, appealing to childhood memories made of cardboard and fabric, video art and book intervention to pinpoint housing insecurity for Haitian and Venezuelan migrants in Chile, evocating Afro Caribbean conditions of housing and its continuities in the Americas. Similarly, ¿Cuánto cuesta el cielo? exposes migration complexities on identity rights. Displaying written messages in both Spanish and Krèyol, a visual litany –and holler– is offered to the identity document. Drawing on García Peña’s concept of Afro Latinidad that posits the nation as an insufficient rubric from which to understand human lived experiences (2022), I argue that Pirela’s artwork reclaims visibility to challenge state policies, and, in turn, contests the intermittent references to afro descendants in Venezuelan culture (Valladares-Ruiz 2013).

Te Espero en la Guerra: Historical Memory and the Colombian Civil War

Rosa Martinez, Graduate Student, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY

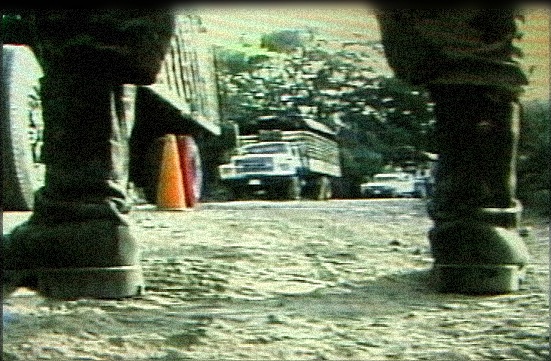

We tell each other stories not only to live, but to fight. Over the last century, the filmmaking process has never been too far from political processes, serving as a vector through which countries negotiate and re-negotiate their self-image. Cultural production can be a form of collective resistance to hegemonic presentations of a nation’s history, especially nations that have undergone mass traumas, such as Colombia. This essay aims to analyze various Colombian films while asking the following: How have films depicting the Colombian Civil War shaped the country’s public opinion and nation-building? In the seven years since the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC-EP), a Marxist guerilla group, agreed to a peace deal, it seems an era of optimism has dawned on a nation where violence and discohesion had become ubiquitous. In 2022, Colombia elected its first ever leftist president, Gustavo Petro, whose vice president, Francia Márquez, is the first ever Afro-Colombian to hold the nation’s second-highest office. However, uncertainty still looms, as indigenous activists are actively persecuted while many former FARC rebels argue that they are being left behind by a fraught peace process. Drawing from various critical works on historical memory, this essay will analyze films such as Patricia Castano and Adalaida Trujillo’s War Takes (2001), Miguel Salazar’s Ciro (2018), and Marta Rodriguez’s Camilo Torres Restrepo, el amor eficaz (2022), exploring how their aesthetic decisions shape the living memory of Colombia’s past, present, and future.

—

November 6

South & About! is a student-organized research workshop on the arts from Latin America and the Caribbean. This program invites graduate students and emerging scholars in art history and related disciplines to participate in informal discussions amongst their peers.

Black Art and Modernization in Brazil: Arthur Ramos’s Study of Afro-Brazilians through Medicine, Education, and Art

Lynne Lee, PhD Candidate, Rice University

In the first half of the twentieth century, intellectuals and technocrats in Brazil spearheaded a national eugenic movement to whiten their population as part of their modernizing endeavors. In this context, medically trained scholars investigated the culture of Afro-Brazilians whom they sought to reform through various disciplines. Among them, Arthur Ramos (1903-1949), a multidisciplinary scholar originally trained in forensic medicine, published in 1949 “Black Art in Brazil,” one of the first texts analyzing Afro-Brazilian religious artifacts as art. His collection of Black art comprises over 140 objects used by Afro-descendants in Brazil and Africa. This paper investigates how Ramos, a protagonist of modernization in 1930s-40s Brazil, instrumentalized Black art to validate claims of Afro-Brazilians’ cultural inferiority and promote eugenic policies that sought to eradicate “undesirable” traces of their cultures.

Although Ramos rejected biological determinism, he considered that Afro-Brazilians were still trapped in a primitive mentality and had to be modernized with the help of educators and physicians. Throughout the 1930s, he directed state-sponsored interventions in schools in Rio de Janeiro to teach mental hygiene and ensure children’s growth into model citizens of a modern Brazil. By parsing Ramos’s educational and medical publications alongside his writings on Afro-Brazilian art, I unveil unsuspected connections between ideals of mental health promoted in the former and aesthetic standards applied in the latter. Ultimately, I demonstrate how these seemingly unrelated studies are animated by the shared ambition to transform Brazil into a modern state according to European models.

Transnational Surrealisms: Re-positioning Violeta Parra’s Arpilleras

Cristalina Parra, MA Student, The Institute of Fine Arts, NYU

This essay studies the work of Chilean artist Violeta Parra (1917-1967), who, from the 1930s through the 1960s, was inspired by folklore, migration, social upheaval, and the tension of the rural/urban in Latin America’s modernizing 1900s. While Parra’s work as a singer-songwriter is internationally recognized, both her career in the plastic arts and her role in the transnational Surrealist movement need further exploration. In the early 1960s, when she already had a flourishing international career as a musician, Parra began making songs that paint themselves, or “canciones que se pintan.” The artist took up painting, sculpture, and embroidery as mediums to represent the themes she had previously only explored musically. Engaging the creative political tools of the Surrealist marvelous, Parra kept folklore at the center of her practice to create a defiant artistic expression against the loss of Latin American cultural heritage. Parra’s early life in the Chilean countryside inspired the themes of her pieces. Parra’s adult life in Paris and the connections Europe facilitated with Surrealists like Roberto Matta and Alejandro Jodorowsky inspired her style. Violeta’s 1964 exhibition in the Musée d’ arts décoratifs of the Louvre was the apogee of her career in the visual arts. The poster she embroidered for the show depicted a giant eye, and it was quintessentially Surrealist. The works on show followed the Surrealist trend, and they depicted Latin America’s ancestral images: musicians, rural ceremonies, animals, festivities, and spiritual scenes. Parra’s thick wool stitches on burlap, delicate macramé, and vibrant paints bring Latin America’s modernizing 1900s to life. To elevate our understanding of Parra’s visual arts and reposition the artist within the conversation of transnational Surrealisms, this essay will examine three pieces that were exhibited both in Parra’s 1964 Louvre exhibition and in the 57th Venice Biennale: Combate Naval I (1964), El Circo (1961), and El Árbol de la Vida (1963).

—

October 2

South & About! is a student-organized research workshop on the arts from Latin America and the Caribbean. This program invites graduate students and emerging scholars in art history and related disciplines to participate in informal discussions amongst their peers.

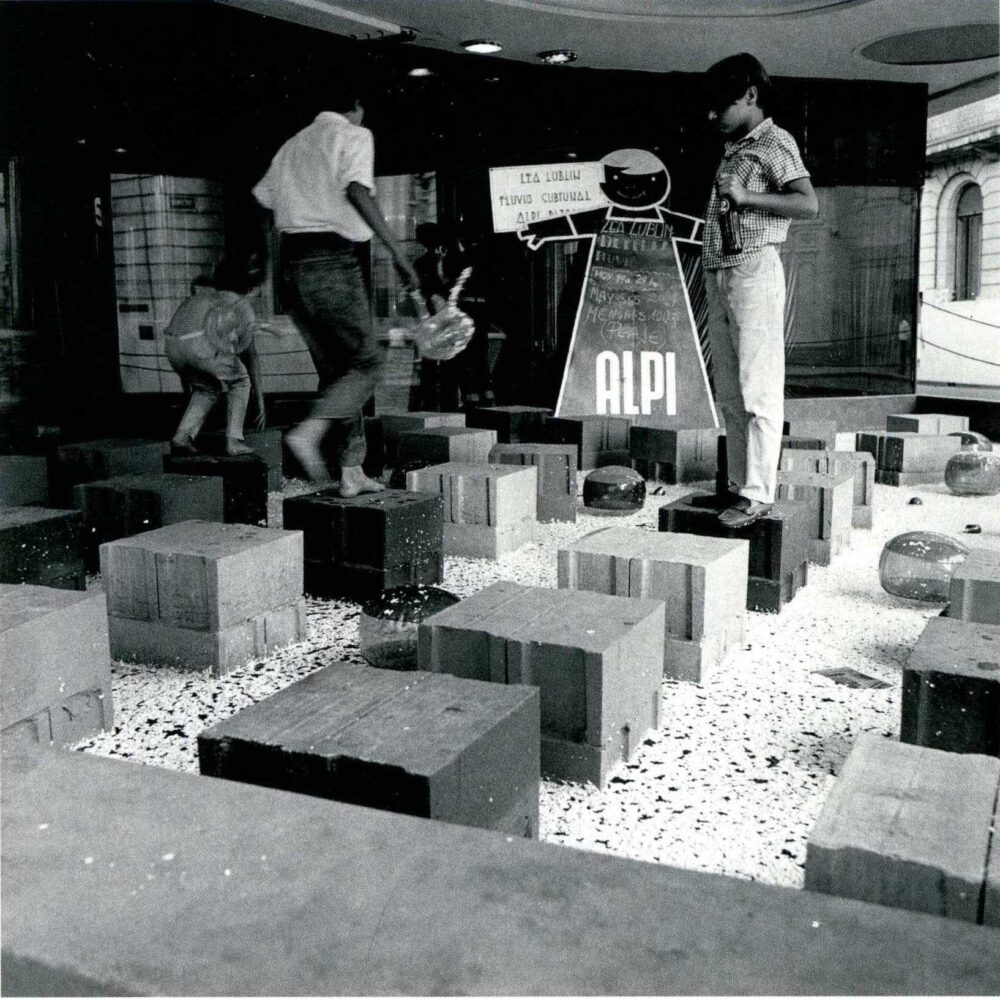

Anagrammatic Production: Lea Lublin’s Fluvio Subtunal (1969)

Jonathan Mandel, PhD student, Princeton University

In December 1969, officials in Argentina’s military government converged on the cities of Santa Fe and Paraná to celebrate the completion of an ambitious infrastructure project: the Túnel Subfluvial Hernandarias, a tunnel providing the country’s first roadway across (or rather, beneath) the Paraná River. As part of a week of festivities, the artist Lea Lublin was invited to produce the work Fluvio Subtunal, a multisensory environment created in an empty department store in central Santa Fe, which she described to the press as a “parallel tunnel.” This paper takes Lublin at her word and treats Fluvio Subtunal as an infrastructure project in its own right, drawing from Brian Larkin’s formulation of infrastructure as “promising forms” through which political rationalities are rendered sensible. By attending not only to the formal dimensions of the work, but also to the assemblage of institutions and individuals that Lublin forged in order to realize Fluvio Subtunal, this paper brings into focus a political tactic that can be described as “anagrammatic” in the artist’s reordering of the political rationality promoted under the Onganía regime.

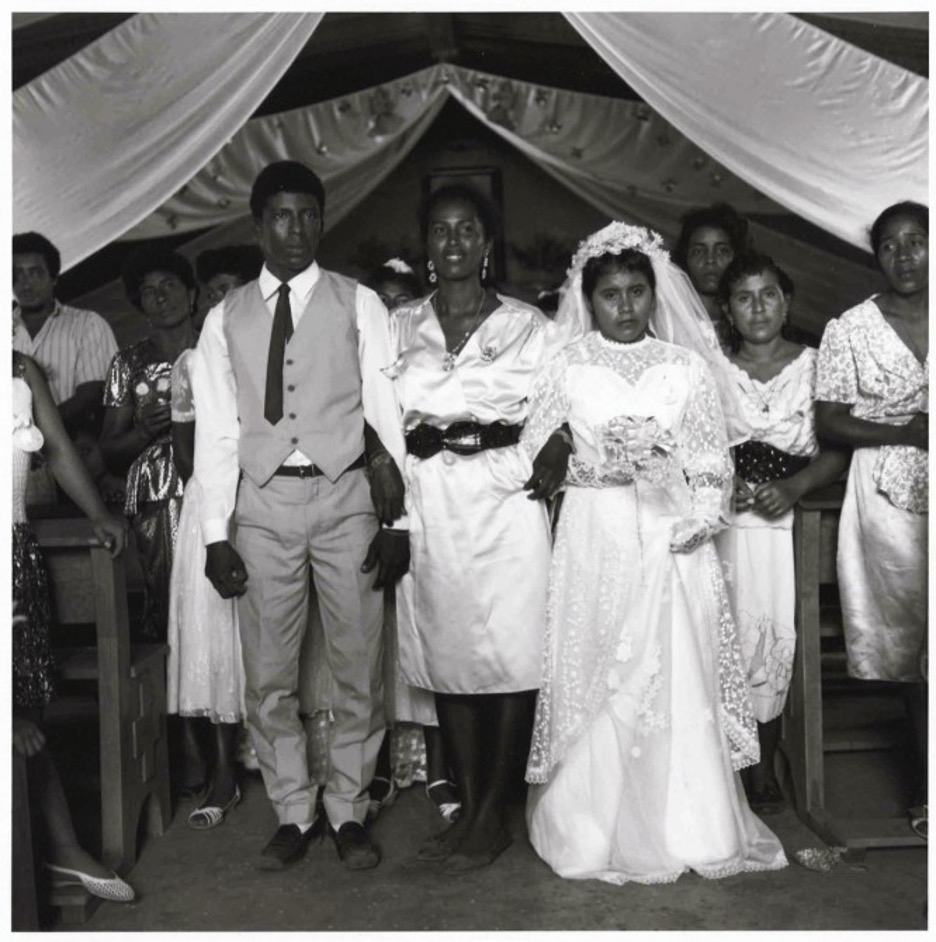

Black Atlantic Ecologies: Marriage, Portraiture, and World-Making in Black and Indigenous Mexico

Bianca Morán, PhD student, The Graduate Center, CUNY

What does a new world identity tell us about the construction of Blackness and the social worlds created to sustain Black life in Mexico? How does indigeneity, both African and American, challenge notions of Latinidad? Through reading the images in Tony Gleaton’s oeuvre alongside earlier images of the African diaspora in Mexico, I hope to articulate a genealogy that both marks the presence of Afro-descendants and highlights the endurance of Black and indigenous life in the midst of coloniality. I situate Gleaton’s image within the scholarship of colonial Mexico, early twentieth-century Mexican portraiture, and contemporary data on Afro-Mexicans. I am interested in thinking about marriage and social life alongside indigenous and Black world-making, and the role of portraiture in an effort to unsettle data. Through the conceptual framework of the shoal, as articulated by scholar Tiffany Lethabo King, I hope to outline the concept of Afro-Atlantic ecologies as intimate and intricate systems of co-existence and convergence between indigenous people of both Africa and the Americas. Mexico operates as the environment that shapes an Afro-Atlantic ecology which aims to illuminate the ways in which Africans and their descendants find ways of living and life in community with indigenous people of the Americas. Specific to this study is the role of marriage, both cultural and ceremonial, in defining the spaces where an Afro-Atlantic ecology emerges. Instead of relying on a scientific approach to investigating ecology, I am thinking here of how these systems are represented visually, and what these images offer the historical record that may otherwise go uncaptured. Importantly, I want to consider portraiture as an intervention and to situate portraits as a mode of visualizing life and the networks of living.

—

Archive

Spring 2023 – Fall 2022 – Spring 2022 – Fall 2021 – Spring 2021 – Fall 2020 – Spring 2020 – Fall 2019 – Spring 2019 – Fall 2018 – Spring 2018 – Fall 2017 – Spring 2017